War games: the Canadian airmen who took Durham by storm

"Durham! That's the place where the player plays against six others…

…and seven wooden posts."

- an unknown Canadian airman.

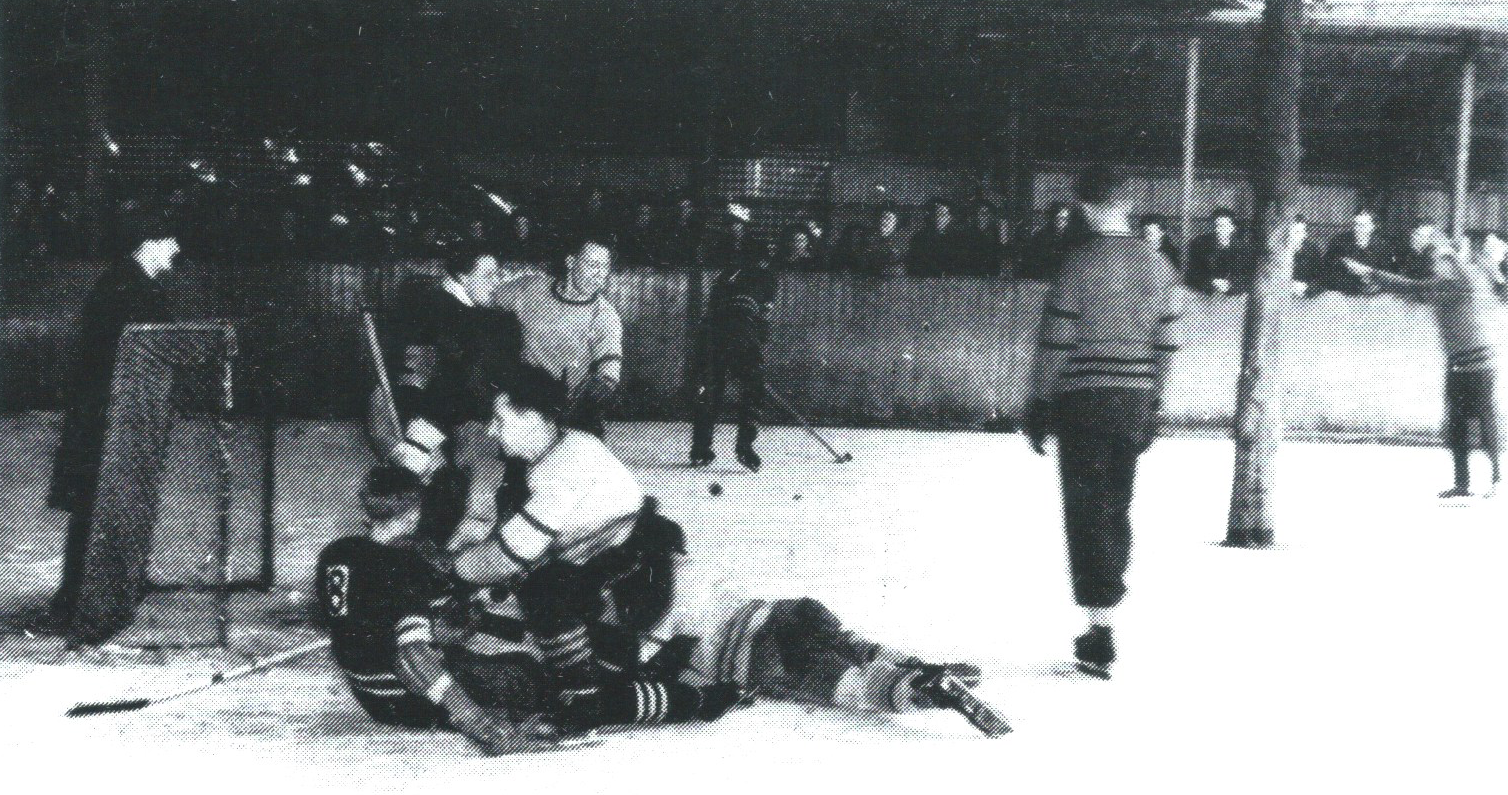

A well-known historic image of the Durham rink during an R.C.A.F. hockey game, likely the 1945 inter-squadron league final, and featuring the infamous wooden posts. Some original posts were preserved in the rink’s plant-room until the 1990s.

Photo: Durham Ice Rink programme

Journeying south from Durham on the A1(M), you might spot ‘low-flying aircraft’ signs and occasional wind socks along the way.

While these nondescript grassy airfields and the odd operation Royal Air Force base dotted north-south across the North Yorkshire countryside may seem pretty insignificant now, these former World War 2 bases, and those who served at them played a defining part in Durham’s ice hockey story.

During the early years of the war, thousands of Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) personnel had already made their way over the North Atlantic to serve shoulder-to-shoulder alongside British and other allied forces on British soil. Many of these British-Canadian units were positioned at these northern airfields, including RAF Leeming and RAF Middleton St George, the latter of which sat just over the Durham-Yorkshire border, and is now more familiar to us as Teesside International Airport.

Like moths to a flame, war or no-war, Canadians are naturally going to seek out somewhere to play hockey. For those based at the North Yorkshire airfields, Durham, with it’s somewhat rudimentary, but perfectly serviceable ice pad was the perfect and only place where they could lace up their skates during their down-time.

For the Canadian airmen stationed in the UK, hockey was more than just a game—it was a piece of home. In the midst of wartime pressures, Durham’s ice rink became their escape. To them, it felt familiar, despite being in a strange land thousands of miles from Canadian soil.

And within a few months, in the most unlikely of settings, it would also be bringing together in one place some of the world’s greatest hockey talent.

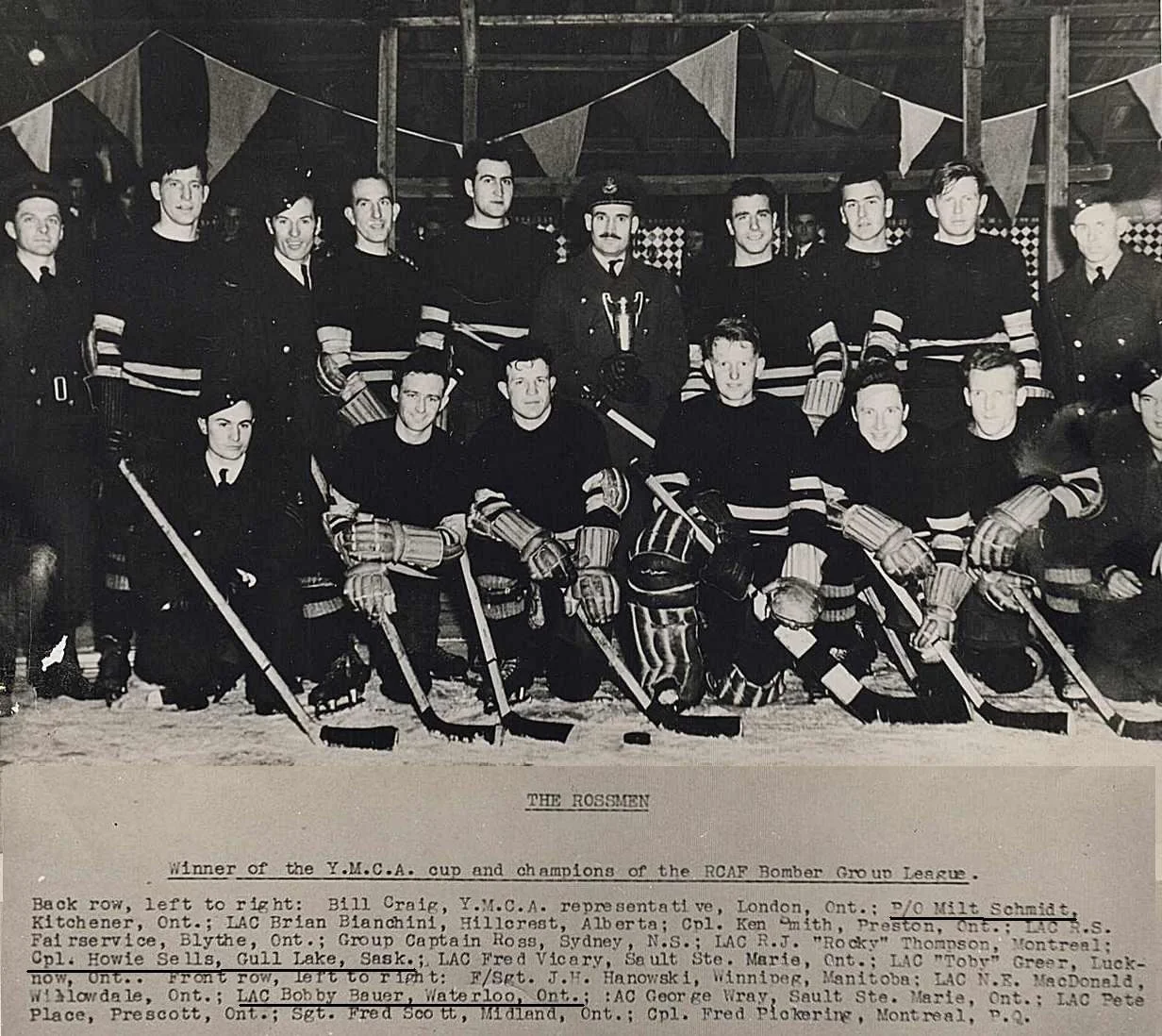

A R.C.A.F. squadron team, (Rossmen), featuring Boston Bruins’ Milt Schmidt and Woody Dumart outside Durham ice rink in 1944.

In 1942, the first R.C.A.F. hockey players arrived at Durham’s rink. Canadian airman Vince Elmer, who was a member of 419 Squadron recalled his first memories of the somewhat unconventional rink to military historian Paul Tweddle, in his book ‘Into the Night Sky’:

“For Canadians this was paradise. Even with the tent over it and the poles down the middle of the ice, we all flocked there in the winter.”

Despite the rink’s unusual features, the newly-arrived Canadian forces quickly fell in love with the place, and with the assistance of the Canadian Y.M.C.A. organisation, a 12-team “Bomber League” was soon established at the rink for forces’ players to compete for an annual trophy. The winners of the ‘Durham’ League would then compete against the winners of two other leagues based at two other ice rinks around the country - one in Liverpool, and one in the London area for the RCAF Overseas Championship.

During the war, these three rinks were some of the few that saw hockey played on them. Some ice rinks had had been requisitioned by the government’s War Office for storage, or even more grimly, in-case they would be needed for the purposes of a temporary, large-scale mortuary. Most others, including the huge arenas at Wembley, Earl’s Court and Harringay had immediately suspended all senior level hockey until further notice.

Not so at Durham, however. The unorthadox rink, with it’s seven wooden poles was in the midst of a full-fledged ice hockey takeover - Canadian style.

Season 1: The ice squadrons assemble

1942/43

On a Tuesday night in early November 1942, the RCAF’s Air Vice Marshall Brookes dropped the puck that started the first of two games in the 1942/43 Y.M.C.A. Bomber League at Durham’s rink.

The first game, between Wing Commander Douglas Bradshaw’s ‘Bombers’ and S/L Ford’s ‘Spitfires’ - both teams named after the type of aircraft that their squadrons flew. Bombers won the first game 6-1, and the second game saw W/C Ferris’s squadron beat the ‘Moosemen’ from Middleton St George, 4-2.

Intriguingly for the winners in the second game, a certain ‘LAC Davy’ is credited as scoring one of the markers for the 408 Squadron team. Could this have been the Ottawa-born Mike Davy who would go on to be a leading figure in founding the Wasps following the end of the war?

Strict restrictions imposed by War Office meant that none of these games could be publicly advertised in order to keep squadron movements classified, and even within the RCAF’s own internal newspaper ‘Wings Abroad’, games at Durham were simply, and intriguingly referred to as being played ‘Somewhere in Northern England’ so as not to give away the location of the Durham rink and minimise the risk of it becoming a potential target in Luftwaffe air-raids.

That meant, that despite some of Canada’s top hockey talent chasing pucks behind closed doors in hundreds of games over a three year period, in the main, only a handful of people actually witnessed what was described as “some of the best hockey in the world” taking place at the unlikely location of the Durham ice pad.

An operations record from No. 403 Squadron, based at Catterick and Hartlepool. Dated 17 November 1942 among various flying logs, the report details the squadron’s hockey team’s visit to Durham for their weekly hockey game, only to discover their opponents hadn’t turned up.

R.C.A.F. ‘6 Group’ to be established in Northern England

By late 1942, plans were drawn up which would make a significant change to RCAF operations in England - and one that would end up bringing some of the finest National Hockey League players to Durham. Up until now, Canadian units had been wholly integrated within British units and squadrons, scattered across a wide array of RAF operations. Canada was keen to demonstrate its sovereignty and operational independence, while Britain needed to maximise the effectiveness of the significant, and growing Commonwealth contributions to the war effort.

The result was the formation of RCAF ‘6 Group’ at the end of 1942. This group was exclusively composed of RCAF personnel, essentially ‘taking over’ a significant number of RAF airfields to operate from. Crucially, it allowed a large, cohesive formation of Canadian air personnel to operate as one under their own command but still receiving orders from RAF Bomber Command higher up the chain. This not only boosted Canadian national pride and also served to demonstrate Canada's capability and autonomy within the Allied forces

Group 6 would quickly established operational bases, some of which were hastily constructed specifically for them, mostly in an area concentrated between York in the south and Darlington in the North.

R.C.A.F. map of the ‘6 Group’ bases and satellite stations. These bases, chosen for their proximity to the English North Sea coast would be used for thousands of bombing and reconnaissance missions for the duration of the war by Canadian forces.

Autumn 1942: The ‘Kraut line’ trio set sail for England

At the same time, heading over the Atlantic from New York aboard the RMS Aquitania - with 8,000 other North American troops - were two of the National Hockey League’s ‘all-time greats’. and a third not too far behind. They were Milt Schmidt, Woody Dumart, and Bobby Bauer, also known as ‘The Kraut Line’.

Milt Schmidt, Bobby Bauer and Woody Dumart, 1942

Childhood friends from the Kitchener-Waterloo area in Ontario and all of German heritage, their close relationship from a young age helped them develop a nearly intuitive understanding of each other's styles puckchasing as teenagers. This was played out as professional hockey players, collectively leading the Bruins to two Stanley Cup victories in 1939 and 1941. As goal-scoring dynamos, during the 1939-1940 NHL season, the trio achieved a rare feat by finishing first, second, and third in the league's scoring—Schmidt led the league, followed by Bauer and Dumart, an unprecedented accomplishment at the time.

In February of 1942, before pausing their professional and lucrative hockey careers to join the war effort, they played in one last game that featured one of the most memorable moments in NHL history. In front of over 10,000 fans, the encounter vs Montreal Canadiens was their final swansong on the Boston Gardens ice before they themselves were set leave for Europe and whatever the war might bring.

“I don’t think I’ll ever forget what happened,” said Schmidt, recalling the end of the game’s iconic events in an interview shortly before he died. “The players on both teams lifted the three of us on their shoulders and carried us off the ice and the crowd gave us an ovation. A man couldn’t ever forget a thing like that.”

Though they didn’t know it at the time, the next time they would be hitting a puck again, it would be in a place that was a world apart from the glitz and glamour of the 1940s NHL, and a place that they probably hadn’t even heard of.

They were about to see them spend three seasons playing clandestine top-secret wartime hockey at Durham - in the little ‘big top’ ice rink by the River Wear.

Dumart, Bauer and Schmidt in their R.C.A.F. uniforms. R.C.A.F. Archive Photo

Schmidt and Dumart embarked for England first. Bobby Bauer followed a few months later, held back on Canadian soil temporarily.

As teenagers, they had been inseparable. As hockey players, they had never played apart. In a dispatch cabled back to Canada, a Canadian Press correspondent remarked:

“Off the ice or on, this is the farthest Schmidt and Dumart have ever strayed from Bobby Bauer, the right winger of the trio”.

Schmidt and Dumart initially both had ground crew roles as physical training instructors, and were posted to their separate squadrons. Schmidt to Middleton-St-George with 419 (now Teesside Airport) and Dumart to Linton-on-Ouse. Bauer would soon also join his line-mate and Boston buddy at Middleton.

In his physical trainer role in the R.C.A.F, Schmidt was obviously keen to take part in, and encourage as much recreational sporting activity on-base and off-base as he could. As a Canadian (and NHL mega-star), he was also itching to get back on the ice.

A short history of ice hockey in Durham published in a 1985 of Ice Hockey News Review, highlighted a fantastic anecdote from rink boss of the time Tom Smith, featuring a remarkable exchange that his grandfather ‘Icy’ had with the NHL legend at the Durham rink: the story goes that Milt had arrived at the rink, and enquired if he could maybe referee a game. Unfortunately, ‘Icy’ hadn’t quite realised just who the young Canuck airman in his ice rink was…

"Can you skate?” asked 'Icy'.

''Yes,'' said the young Canadian airman.

"Know the rules?”, retorted 'Icy'.

''Sort of," replied the airman.

"OK, just follow me anyway,'' said 'Icy', ''…What's your name for the game sheet?"

"Ummm…Milt Schmidt?!"

J. Douglas Harvey, another former R.C.A.F. airman witnessed a number of games that Schmidt played in at Durham and recalled in his book ‘Boys, Bombs and Brussel Sprouts’, the peculiarities witnessing the NHL’s finest playing at the war-time Durham rink:

“To watch Milt Schmidt, one of the best centremen ever to play in the NHL, come weaving around those posts at full speed was an awesome sight. At the best of times he was difficult to check, but the seven posts made him unstoppable.

There were hilarious moments as checkers ran into the posts, while Milt dodged and swerved. Since the posts were frozen, the puck ricochetted off them at great speed and in any direction, sometimes in the wrong net. It was the most entertaining hockey I ever saw.”

W/C Carscallen’s No. 424 Squadron of the Topcliffe base (Winners of the first championship tournament at Durham in 1942/43 and captained/coached by Woody Dumart)

By February 1943, the Durham-based ‘Bomber League’ was heading towards the play-off final stages.

Wing Commander Carscallen’s side, who had started the season abysmally had in recent months enjoyed a distinct turn of fortunes. This was mostly down to the recent arrival of Woody Dumart at their base, who took charge of the team and whipped them into shape.

The R.C.A.F. overseas newspaper reported on the new found winning streak of Dumart’s men, who would ultimately go on to win that year’s championship:

“The Carscallen team, which started the season off by losing with a consistency that was heartrending have acquired Porky Dumart, Wilson and Duffield who have been the spearhead of their winning streak When they defeated W/C Fleming’s team 11-2, Dumart was opposed to Milt Schmidt, his erstwhile Boston Bruin’s team mate. In their following contest with the French Canadian squadron, Fred Belanger, who used to chase pucks with the Quebec Aces managed to hold Dumart in-check up to a point but not prevent the Carscallens from winning 6-2.”

Though some may find it difficult to believe, for those who had the privilege of watching him perform in Carscallen’s Topcliffe team, it’s said that Woody Dumart actually played better hockey at Durham than he played as a professional, earning £2,600 a season (in ‘old money’) in the NHL.

…Perhaps the ‘big league over the pond’ should have introduced some wooden posts to liven things up a little?

The grim realities of war

While hockey was a welcome respite for many of the R.C.A.F. crewmen serving during the war, the brutal and tragic reality was that because of the dangers they faced in the skies over Europe, for some, the last game that they ever played would sadly be at Durham.

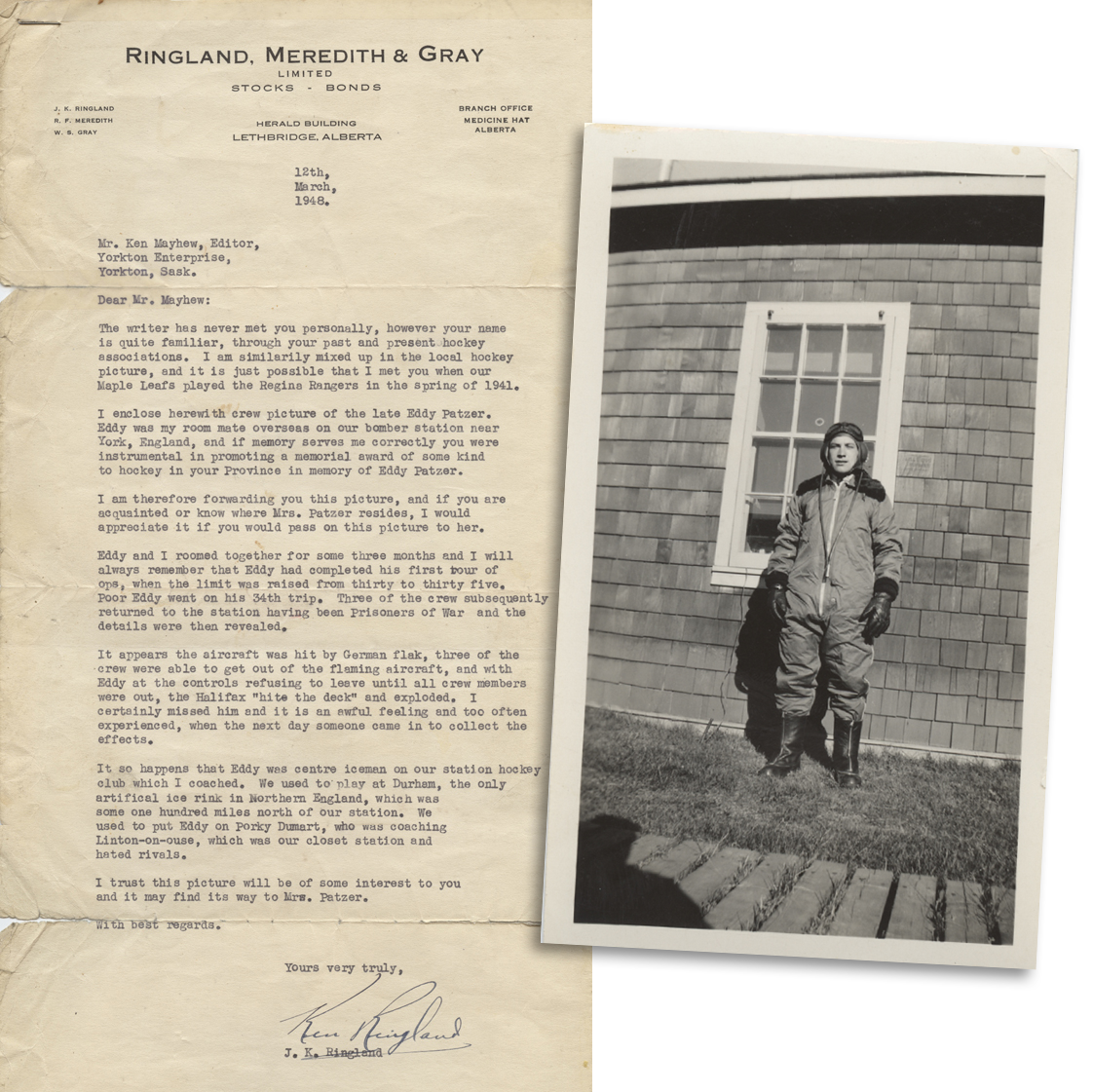

In a postwar letter, dated March 12, 1948, from J.K. Ringland to Ken Mayhew, editor of the Yorkton Enterprise, a Saskatchewan-based newspaper, Ringland, who shares a connection with Mayhew through hockey, reminisces about their mutual acquaintance, the late Eddy Patzer who was killed in action during the war.

Ringland, who was roommates with Patzer at an un-named 6 Group bomber station in during the war, enclosed a crew picture of Patzer, noting his heroism and tragic death after refusing to abandon his aircraft until his crew had escaped.

He ends the letter touching on his and Eddy Patzer’s shared experiences of playing hockey at Durham, and highlighting the inter-squadron rivalry by, noting:

“It so happens that Eddy was centre iceman on our station hockey club which I coached. We used to play at Durham, the only artificial ice rink in Northern England, which was some one hundred miles north of our station. We used to put Eddy on Porky Dumart, who was coaching Linton-on-Ouse, our closest station and hated rivals.

I trust this picture will be of some interest to you and it may find its way to Mrs. Patzer.”

Season 2: The year of the Rossmen

1943/44

The war raged on for another long year and aircraft took off relentlessly from the Group 6 bases, but by autumn 1943, once again, Vice-Marshall Brookes was back at Durham to drop the ceremonial puck and open the second season of RCAF hockey in Durham. This time however, lining up to take the face off in the opening game would be Boston Bruins’ Milt Schmidt.

It was during this season that late-arrival Bobby Bauer made his debut at the Durham rink, reuniting with his Boston line-mates. A handful of young local Durham hockey players, in awe of the hockey that they were able watch on an ‘invite-only’ basis even asked Schmidt to coach hockey-skills clinics for them on winter Sundays - of which he duly obliged.

Is it therefore possible to think that the very first coach of the fledgling and ‘not-yet-named Durham Wasps’ may have been the late, great Milt Schmidt?

Jim Hall, one of the founder members of the Durham Wasps recalled his own memories of the time in 2004:

"If the team were one or two short, the Canadian players used to ask us local lads on the ice to make up the numbers. So we ended up forming our own team in the end.”

Throughout the season, games between squadrons were played 6 days a week at the Durham rink. Unsurprisingly, the two teams that would come out on top by the spring of 1944 were Schmidt and Bauer’s ‘Rossmen’ from Middleton base (named after their Group captain - Air Commodore Arthur Dwight Ross) - and Woody Dumart’s ‘Lancasters’ of Leeming.

Incidentally, by this point, Schmidt had moved up the ranks within the R.C.A.F. to become a fully commissioned pilot officer, which awkwardly meant that when he ran into his former Boston linemates, they were technically obliged to salute him… which likely resulted in some ‘colourful’ on and off ice banter.

March 1944: ‘Canada Day’ celebrations at Durham & the 2nd Canadian Y.M.C.A. Cup Final

Playing a ‘best of three’ series for the championship in March 1944 the two top teams from the Durham league faced-off for the inter-station league title. In the first game the Rossmen shut-out the Lancasters 5-0, however the second game a week later would form part of a rare and rather memorable ‘Canada Night’ - an evening of celebration that had been organised by the Canadian Y.M.C.A. at the Durham Rink - billed as ‘5 hours of entertainment’ for the modest entry fee of a shilling a head.

As the Royal Canadian Air Force Headquarters Band opened up proceedings with a concert of entertainment at 5:30pm, over 800 RCAF servicemen and women and an equal number of Durham civillians were already packed into the small pavillion that surrounded the rink. At 6pm the cup final faced-off infront of the 1,650 strong crowd of eager attendees.

In a rare national report of these usually behind-closed-doors games, the Canadian Press’s Alan Nickleson filed a colourful description of the cup final’s venue, albeit with a slight exaggeration* while maintainting the standard degree of location-vagueness by reporting from ‘a non-specific location in England’:

“The site of play was ludicrous even by the best Canadian standards. As last season, it was staged in a canvas-topped rink with no less than 10* huge tent poles set up down the centre of the ice to hold up the canvas. Human rearguards and their wooden allies presented formidable obstacles to goal-minded opponents.”

The game itself, featuring all three of the ‘Kraut-line’ - albeit on opposing sides did not disappoint. With Woody Dumart the driving force for the trailing team, line-mate Corporal “Scotty” Gourlay fired the Lancasters into the lead with two unanswered markers, but it didn’t hold.

Trailing 2-0 going into final period, the Rossmen pulled one back through Corporal Ken Smith - a former member of the 1937 Ontario Hockey Association champions from Preston - and shortly after, Boston Bruin Bobby Bauer netted the equaliser. Ramping up the pressure, Schmidt fired in two goals in ten seconds to put the Middleton side 4-2 up before Gourlay pulled one back for the Lancasters. Corporal Howie Sells from Sask. was also credited for an outstading game. Final score 4-3 to the Rossmen, to emphatically take the series, and the Y.M.C.A. cup two games to nil.

Intervals between periods were filled with comedy perfomances, and exhibitions by local skaters, including Durham the recently crowned Durham ladies’ champion Emily Ryles, and the undefeated mens’ champion Joe Dixon.

And the fun wasn’t over yet. After the game, the ice surface was divided in two, with everyone in attendance either skating on one side, or ballroom dancing on a floored section to the tunes of the R.C.A.F. dance band. According to those who had the honour of attending, it was “a colossal sight” to witness the evening’s entertainment in celebration of the R.C.A.F. troops and hockey players.

Milt Schmidt, receiving the Y.M.C.A. trophy from Group Captain Ross. Normally these games were played ‘behind closed-doors’, however the 1944 cup final saw over 1,600 in attendance as part of ‘Canada Day’ celebrations at the Durham rink.

Cup Final report from ‘Wings Abroad’ featuring photo of ‘The Kraut line’ in their respective Bomber League team uniforms

The Rossmen team of 1944, picured with Group Captain Ross, and the Y.M.C.A. trophy. Note the bunting in the picture as part of the ‘Canada Day’ celebrations held at the rink for the cup final game.

As winners of the Durham Y.M.C.A. championship, the Rossmen went on to face a squadron from the Liverpool area on 25th February to battle it out in overall RCAF Overseas Championship play offs. In a two-leg semi final the Durham-area representatives saw-off the Liverpool-area team - the ‘Ontario Wolves’ 7-2 in the first game at the Palace Rink in Liverpool with Bobby Bauer bagging a hat-trick.

In the final, also played at Liverpool in front of a capacity crowd, the ‘Durham Rossmen’ faced the ‘Skeeters’ from London. (Skeeters being Canadian slang for ‘Mosquitoes’, so likely a reference to the aircraft the squadron flew). The Rossmen swatted them away however, scoring four goals in quick succession and although Skeeters tried hard to catch up, they never succeeded in gaining the lead and the final score was a 9-5 victory for Rossmen who were crowned overall R.C.A.F. overseas champions to carry off the Edward Trophy - donated by Air Vice Marshall Harold Edward and presented on the night to player-coach Milt Schmidt by Wing Commander H.P. Dunn.

November 1944: Double disaster at the rink

It started out as a normal evening skating session one windswept stormy night in November 1944, but after multiple attempts by mother nature over the years, it would end in much of the ice rink’s infamous canvas ‘tent’ finally being ripped to shreds beyond repair.

From eyewitness reports, the writing was on the wall long before the inevitable happened as sections of canvas tore, the whole structure groaned, and it began to lift and sway under the force of the gales battering it from outside.

The skating continued however. But as a precaution, was paused every 15 minutes to allow instructions to be broadcast over the rink’s loudspeaker of what to do, should the worst come to the worst and the evacuation orders be given.

Thirty minutes before the session was due to end, the moment arrived - skaters scrambling over the barrier to safety as the roof supports began to give way. Ten minutes later with everyone clear of the danger, the holding ropes were reluctantly slashed and the whole thing came down onto the ice with a terrific crash. The largest standing tent in Europe was sadly, standing-no-more.

Even worse was to come however just three weeks later on 25th November. With the rink back up and running following the roof collapse, a carelessly discarded cigarette, dropped by a skater in the rink’s cafe at the end of the Saturday session seemingly started a small fire, which smouldered overnight and by Sunday morning had erupted into a blaze.

Watchers from the Royal Observer Corps, mere metres away over the other side of the road in their Providence Row HQ were thankfully in observant mode, and put in a call to the National Fire Service, who arrived at 8am to find the northern end of the rink in flames.

No one was more surprised than the firemen themselves. It was a standing joke at the Durham fire station that when ever a call was received they would immediately ask “ice rink?” This time it was no joke. After an-hour battling the blaze, one end of the rink’s pavilion, including the cafe and kitchen were completely burned down and almost one-third of the four inch thick ice pad was melted down to the pipes.

Despite the rink being partially wrecked, one memorable comment on the situation was made by one Canadian airman, familiar with the rink’s resolute proprietor, who was overheard to say to one of his comrades:

“I bet the old boy still has skating going on this afternoon.”

He was wasn’t wrong. Old ‘Icy’ had the ‘good half’ of the rink up and running with an even bigger crowd than usual that very same Sunday afternoon.

Skaters on the ice following the November ‘44 fire. The damage to the pavillion is clearly visible in the background. Credit: Alan Ramsay

Season 3: An ‘al fresco finale’

1944/45

March 1945: By now, things were looking tentatively brighter on the war-front, and perhaps, just perhaps the end was in sight. Paris had been liberated the summer previously, and Allied forces were now paving the way to cross the Rhine, an important strategic defence line for German forces. Hitler’s suicide in a Berlin bunker was a matter of weeks away. From the airfields of Yorkshire, The R.C.A.F. squadrons based at 6 Group continued with their strategic missions over mainland Europe, but there was no let-up on the hockey-front either at Durham, despite the rink now having no roof. The finalists for the third Bomber League season had been decided.

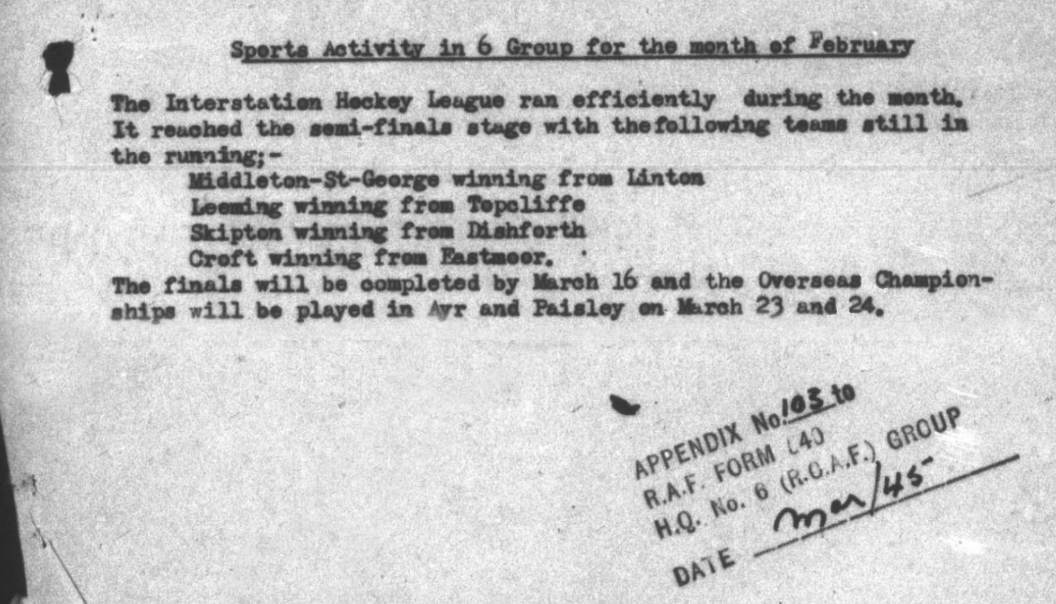

A R.C.A.F. internal communique detailing the hockey league’s quarter-finals’ progress.

With squadron teams from Linton, Topcliffe, Dishforth and Eastmoor dumped out in the last-eight stage in, the final four, Middleton and Leeming beat Skipton and Croft for the rights to take part in what would be the final showdown at the Durham rink over the usual three game series. It’s said that of all three sets of finals’ held at Durham this was possibly the most outstanding one - and this time, ‘al-fresco‘.

Leeming, playing under the name of their station commander, G/C Millward, known as “Millward’s Pucksters” and captained by F/S Jack Cain eked out a win in the first game 3-2. The winners of game one featured two former NHL’ers: Alfie Pike and Lloyd Gronsdahl. Pike, a former New York Ranger also happened to be licensed mortician in the offseason - earning himself the dubious nickname of “The Embalmer" while Gronsdahl, a minor-league winger had also played ten games for Boston Bruins during the 41/42 season.

Despite the win, Millward’s Leeming team suffering what was described as a “sound shellacking” by astute Canadian observers in the second game, as Milt Schmidt’s Middleton squad representing G/C Harold Miles administered a 7-1 drubbing in the re-match.

And so unlike the previous season, this final went to the third and final game, played March 16, 1945. Leeming, without the services of Alf Pike for this one faced three NHL’ers in the Middleton squad for the final game, Roy Conacher, another former Boston Bruin and Hockey Hall-of-Famer; former Montreal Canadien, Jimmy Haggerty, and of course, Milt Schmidt to complete the all-star line up.

While Schmidt’s Miles’ men carried most of the play, they struggled to shake off the close-checking of Leeming and the game was goalless going into the final third. By this point, Millward’s side had also lost the services of their captain, Jack Cain. With little sign of either team breaking the deadlock, Leeming defender Jimmy Colfer picked the puck up on a breakaway with ten minutes left to go and rifled it past the Middleton minder Len Pinkney. With his opposite number Jean Louis Dion in the Leeming net keeping Milt Schmidt and company at bay while shorthanded, seconds after emerging from the sin-bin Cpl. Ted Redmond scored the second and with the minutes ticking over into single figures, Gronsdahl netted the third and final goal to seal the game - and the championship.

Medals were awarded after the bruising encounter to both teams by Air Commodore Dunlap, of Vancouver with the winners heading North this time to take part the Overseas Championship finals, held at Paisley and Ayr in Scotland the following week.

An NHL all-star line up at Durham following the 1945 final, and the various teams that they were famously associated with.

From left to right: Roy Conacher (Boston Bruins); Alf Pike (New York Rangers); Paul Platz (Providence Reds); Jimmy Haggerty (Montreal Canadiens); Bob Whitelaw and Sid Abel (both Detroit Red Wings); Frank Boucher (RCAF Flyers); Lloyd Gronsdahl (Boston Bruins); Ernie Trigg (AHL Cleveland Barons); Milt Schmidt and Woody Dumart (Boston Bruins).

World War II in Europe officially ended with the unconditional surrender of Germany on May 7, 1945, and formally ratified the following day.

Of the ‘Kraut Line’ trio, Bobby Bauer was the first to head back to Canada, in July of 1945. He finished the hockey season in hospital, with sciatica of the back and leg, brought on by an old hockey injury.

Schmidt and Dumart followed in October, sailing to Halifax aboard the Ile de France. With no more need for censorship, it could finally revealed that they’d served their three years in Yorkshire with the Sixth Canadian Bomber Group…

…and played three seasons of hockey ‘somewhere in Northern England’ at a place called Durham.

A final ‘hurrah’: R.C.A.F. players on Durham ice at the end of the war. The ‘patched’ up section of the rink, damaged in the fire the previous November can be seen in the background.

In total, over 500 R.C.A.F. hockey games were played at Durham’s ice rink during World War 2 (and all of them referee’d by Durham Ice Rink’s John James Smith).

In excess of 35 National Hockey League, and other top-level Canadian players graced the ice at Durham during this period.

6 (R.C.A.F.) Group flew 40,822 operational sorties during their tenure in North Yorkshire and County Durham.

As part of the war effort, 6 Group squadrons took part in significant strategic operations, included raids on U-boat bases in Lorient and Saint-Nazaire, France and night-bombing raids on industrial complexes and urban centres in Germany.

A total of 814 aircraft and approximately 5,700 airmen did not return from operations, including 4,203 who lost their lives.

“…Per ardua ad astra.”

(“Through adversity to the stars” - motto of the Royal Canadian Air Force.)